Holi is one of the major festivals in India and is celebrated with extreme enthusiasm and joy in rural India. Elaborate plans are made to color their loved ones. But this was not to be the case for the 16 women and eight men belonging to the Lambada tribe, who, on the eve of Holi, March 27, 2021, went inside the Amrabad tiger reserve in Nallamala forest, Nagarkurnool district of Telangana, a south-central state of India. The tribals or adivasis went into the forest to pick Mahua flowers which is a major source of livelihood for them. The Mahua flower (Madhuca Indica) is an important forest product for tribal communities who harvest this for food and for brewing alcohol. Classified as a forest produce, Mahua is controlled by state excise laws where permits are issued for collection and storage by charging nominal license fees.

In the middle of the night, while the tribals were sleeping in the forest after collecting flowers, they were suddenly attacked by forest officials and staff. The tribals were ordered to strip and they were beaten up. Victims suffered head injuries such as 48 year-old K Patya, and even a 70year-old woman was also manhandled. The other unnamed adivasi women and men were likewise forced to strip and were tortured.

Days after, despite punishing heat, the aggrieved Lambadas, including elderly indigenous women and many others with injuries on their head and limbs staged a sit-in protest outside the office of the Telangana State Human Rights Commission (TSHRC) in Hyderabad. Protestors recounted how they were assaulted by forest officials. One of the victims, 49 year-old K Anchali said, "We demand the DFO’s [District Forest Officer] resignation and we are filing cases against the forest officials under SC/ST Prevention of Atrocities Act." Based on the complaint of gross human rights violations and obstruction of livelihood of tribals, the TSHRC ordered the Nagarkurnool forest officials to furnish a written explanation about the incident and to be present before the commission at the hearing set on April 26. After meeting with several Telangana tribal associations, Telangana Tribal Welfare Minister Satyavathi Rathod assured the victims that they will be provided medical treatment and appropriate action will be taken against the forest officials who attacked them, assuring justice to the aggrieved community.

But instead, the Lambadas have been booked under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 for unauthorized entry into the tiger reserve, removal/destruction of forest produce, lighting firewood to cook, and carrying weapons inside the tiger reserve. The Lambadas were criminalized and judicially harassed in spite of the fact that the Scheduled Tribes have the right to collect, use, and dispose of "minor forest produce" (which included Mahua flower) from forest lands which is defined as “land of any description falling within any forest area and includes unclassified forests, undemarcated forests, existing or deemed forests, protected forests, reserved forests, Sanctuaries and National Parks” under the Forest Rights Act 2006.

The case of the Lambada people is one among documented cases of violation of rights of other Indigenous Peoples that comprise the 104.3 million Scheduled Tribes (STs) also called tribals or Adivasi in India. They constitute 8.6 per cent of the country’s total population. About 90 per cent of the STs live in rural areas without access to basic facilities and services. Census in 2011 showed that only 59 per cent of the STs are literate, with 68.50 per cent male and female at 49.40 per cent.

The STs supposedly enjoy protection of their land and other social issues under the Constitution’s Fifth Schedule in mainland India and the Sixth Schedule in the Northeast region. No Act of Parliament or of the State Legislature shall apply to a Scheduled Area unless the Governor directs it by public notification and the same can make regulations to prohibit or restrict the transfer of land to non-tribals.

The Provisions of the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 (PESA) gives enormous powers to the Gram Sabha or Village Assembly in relation to land acquisition and approval of plans, program and projects, and PESA is applicable in the Fifth Schedule Areas. In addition, the Ministry of Tribal Affairs was created in 1999 to look after the development and welfare of the STs.

Administrative actions for protection of Indigenous Peoples in India

In February 2004, the Constitution of India was amended to divide the National Commission for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes into two separate commissions (National Commission for Scheduled Tribes, and National Commission for Scheduled Castes) to oversee the implementation of various safeguards provided to them. Special Courts have been set up across the country to try offences committed under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.

The rights of the Scheduled Tribes are also protected under special laws like the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, the Forest Rights Act of 2006, and the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 which are applicable throughout the country. These legislations were passed in the context of historical injustices meted out to the tribals by past rulers and the society. In 1871, the British Parliament had passed the Criminal Tribes Act to classify over 200 tribes as hereditary, habitual criminals and stigmatized generations of these tribal communities.

After independence, the Indian Government repealed the Criminal Tribes Act in 1952 and the so-called criminal tribes were ‘denotified,’ but the Criminal Tribes Act was replaced by the Habitual Offenders Act, 1952 which instead of easing their lives, only ended up re-stigmatizing them.

Since then, the number of crimes and atrocities against the Scheduled Tribes has steadily increased in recent years. According to the report “Crime in India 2020” of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) under the Ministry of Home Affairs, the number of crime/atrocities committed against the Scheduled Tribes was 6,528 cases in 2018, 7,570 cases in 2019, and 8,272 cases in 2020.

The creation of the NHRC

On October 12, 1993 the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) of India was established under the Protection of Human Rights Act (PHRA), 1993 which was amended in 2006 and 2019. Section 2(1) (d) of the PHRA defines Human Rights as the rights relating to life, liberty, equality and dignity of the individual guaranteed by the Constitution or embodied in the International Covenants and enforced by the courts in India. With its ‘A’ status given by the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI) in Geneva, the NHRC is in compliance with the Paris Principles which are the international minimum standards required for human rights institutions to be considered legitimate, credible and effective in human rights promotion and protection.

The NHRC of India is headed either by a former Chief Justice or a former Judge of the Supreme Court, with five (including three non-judicial) members who are appointed by the President of India upon recommendation of a committee consisting of the Prime Minister as Chairperson. The five members of this committee are the Speaker of the Lower House of Parliament, Minister of Home Affairs, Leader of Opposition in the Lower House of Parliament, Leader of Opposition and Deputy Chairperson in the Upper House of Parliament. The seven ex-officio members in the NHRC are the Chairpersons of the National Commission for Backward Classes, the National Commission for Minorities, the National Commission for Scheduled Castes, the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes, the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights, the National Commission for Women, and the Chief Commissioner of Persons with Disabilities.

Roles of NHRC in addressing human rights violations

The NHRC is tasked to inquire on petitions concerning violation of human rights, or abetment, or negligence in the prevention of such violation by a public servant. It can also intervene in any proceeding involving any allegation of violation of human rights pending before a court with the approval of such court. It can visit any jail or other state- controlled institutions where persons are detained for purposes of treatment, reformation or protection, to look into the living conditions of the inmates and make recommendations to the Government.

The Commission reviews the safeguards provided by the Constitution or any law in force for the protection of human rights and recommends measures for their effective implementation; and reviews also the factors, including acts of terrorism that inhibit the enjoyment of human rights and recommend appropriate remedial measures.

The Commission studies treaties and other international instruments on human rights and makes recommendations for their effective implementation and undertakes and promotes research in the field of human rights. Through publications, the media, seminars and other available means, the NHRC broadens human rights literacy among various social sectors and promotes awareness on safeguards available for the protection of rights. It encourages the efforts of non-governmental organisations and institutions that work in the field of human rights.

Although the NHRC can investigate violation of human rights of all including the Scheduled Tribes, the Government of India established the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST) in February 2004 with the mandate to safeguard the rights of the Scheduled Tribes. However, the NCST presently does not have the necessary members and is functioning with only the Chairperson and one member.

Taking action on human rights violations: IRAC’s Intervention

Upon learning of the human rights violation cases of tribals, the Indigenous Rights Advocacy Centre (IRAC) filed a complaint before the National Human Rights Commission against the erring forest officials responsible for the attack on the Lambada tribals (NHRC Case No. 1086/36/22/2021). Each day, IRAC staffs monitor and document cases of human rights violations including violence against, criminalization of, and impunity against Indigenous Peoples in India.

They try to overcome the challenges of monitoring cases of human rights violations in the country’s vast geographical expanse. IRAC’s intervention in cases and engagement with the NHRC covers the length and breadth of the country from Assam/Manipur in the northeast to Gujarat in the west; from Jammu and Kashmir in the north to Tamil Nadu in the south.

Brief introduction/background of IRAC

IRAC was established in the year 2020. The vision of the organization is to promote, protect and defend the rights and interests of the tribal communities/Adivasis/Indigenous Peoples in India. As a means of achieving its objectives, IRAC seeks to combine practice, research, advocacy and collaboration as an effective method to promote, protect and defend the individual and collective rights of Indigenous Peoples.

IRAC adopted a monitoring system using secondary sources such as credible national as well as regional newspapers, online news portals, and social media handles of prominent human rights non-government organizations (NGOs) and rights activists. Primary information is collected through a network of NGOs and activists/community leaders at the grassroots level, and runs a free Legal Helpline where cases of human rights violations are reported. Verification of the secondary sources is done through a network created by IRAC composed of journalists and human rights activists who work effectively and share information with IRAC. Several of the cases documented by IRAC have led to filing of complaints before the NHRC which is mandated to protect, defend and promote human rights under the Protection of Human Rights Act of 1993.

The interventions made by IRAC were appreciated and supported by NHRC as they complement each other’s tasks and advocacies. The cases forwarded by IRAC to NHRC tested the latter’s determined pursuit of its mandate as it has all the powers of a civil court trying a suit under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1908.

After receiving a complaint, the Commission can call for information or report from the Central or State Government or any other authority within a specified time. If reports sought are not submitted on time, the NHRC issues reminder or summons the officials for physical appearance before it at the New Delhi office. After completion of enquiry into the human rights violation, the Commission can recommend to the concerned Government authority for payment of compensation to the complainant/victim and to initiate proceedings to prosecute the perpetrator(s). The NHRC can also approach the Supreme Court or the High Court concerned for such directions, orders or writs as that Court may deem necessary.

Between July 1, 2021 and December 31, 2021, IRAC’s database reveals that the organization intervened in 77 cases of human rights violations against Indigenous Peoples by way of complaints filed before the NHRC.

The IRAC intervened in these cases to ensure justice, claim reparation for the victims and their families, and to establish accountability by punishing the culprits to reduce, if not to eradicate impunity. At least 27 235 Indigenous Peoples are direct beneficiaries of these 77 cases.

Of the total interventions, 44 out of 77 cases, or 57 per cent were on criminalization of Indigenous Peoples committed by the police, forest department and other public officials. The remaining 33 cases were atrocities committed by non-state actors/non-tribals and denial of basic documents and welfare schemes by the Government. The IRAC regularly followed up these cases with the NHRC to ensure justice for the indigenous victims.

The Need for Continuing Advocacy for Adivasis’ Rights

The list of cases documented and monitored by IRAC illustrates the breadth and depth of violation of individual and collective rights being committed against Indigenous Peoples despite laws to protect them and their territories and resources.

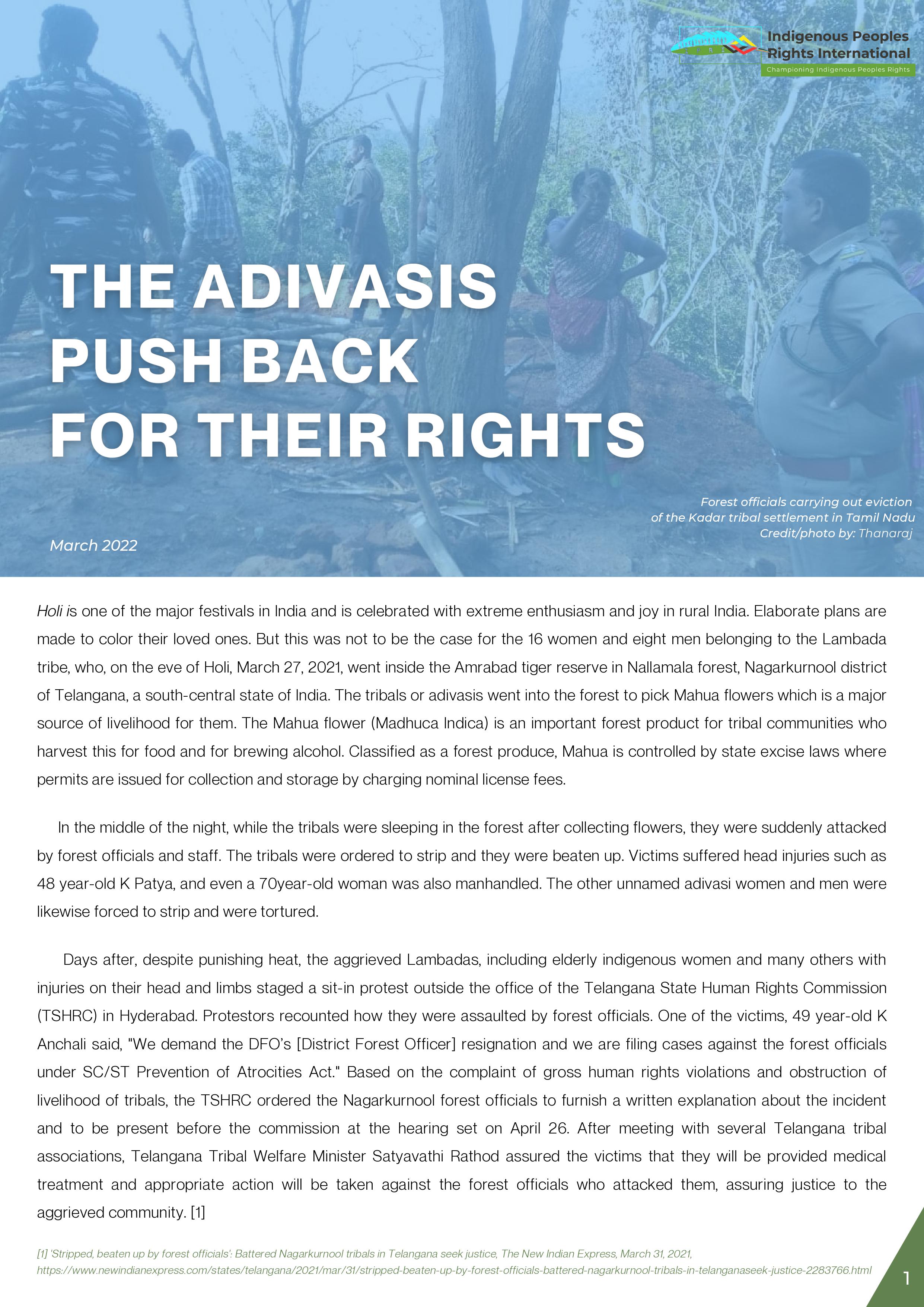

Besides the torture of several men and women of the Lambada tribe in Nagarkurnool district, Telangana by forest officials, the list includes the case of forest officials and staff who forcibly evicted tribal people by burning down their huts in Palampattu hills in Tamil Nadu in July 2021.

Then there was the case of bonded labour at Pilanje Budruk Chinchpada village in Bhiwandi, Thane district of Maharashtra. For generations, 18 Katbari tribal families were inhumanely treated with public flogging, starvation, and enslavement by two brothers who are contractors operating a brick kiln factory and sand stone quarry. The owners, Chandrakant and Rajaram Patil forced the tribals to work without proper pay, food or water and forced them to work to repay loans allegedly taken by their forefathers, and prohibited them from looking for other jobs. All those times, the brothers were in collusion with the police.

Custodial death due to alleged torture in police custody was the case of 35 year-old Bhim Kale, a member of the Phase Pardhi tribe. He died while in illegal police custody at Vijapur Naka police station in Solapur district, Maharashtra on October 3, 2021. A 19-year-old tribal girl was confined and sexually abused by her employer in Kerala. After escaping she reached her home in Madhya Pradesh but the Village Panchayat passed an order to either return to her employer or pay him Rs 2 Lakhs(200000 INR). Likewise, the case of a 35-year-old tribal woman who was brutally raped in Basna in Mahasamund district of Chhattisgarh on September 17, 2021 is a stark example of violence against indigenous or tribal women. These cases involve grave violation of the human rights of the survivors and their families.

The list of cases documented by IRAC is a long one: threat of forced eviction, alleged fake encounter killing, tortured to death in police custody, torture by police (not leading to death), tortured to death by non-tribals, torture (not leading to death) by non-tribals, arrest on false charges, filing of false charges (not leading to arrest), malnutrition deaths/starvation, land grabbing by the forest department, injury in police firing, killing by Maoists, harassment of indigenous human rights defender, and denial of right to education.

Other cases are mainly related to denial of government food grain, official documents, development schemes and facilities. The interventions made by the IRAC range from civil and political rights to economic, social and cultural rights. These manifest the continuing denial and repression of the collective rights of Indigenous Peoples to their lands, territories and resources, and their traditional livelihoods. Likewise, these cases are also clear violations of the obligations of the State of India under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination which India has ratified.

In the case of the victims of bonded labor, a long detailed list of questions on violation of or compliance with labor laws and Supreme Court orders was issued for a thoroughgoing investigation to verify and validate commission of crime by the accused sibling contractors and inaction of officers and collusion with police elements.

The NHRC, while reminding the concerned authorities of their tasks of adhering to the law, particularly provisions on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, likewise orders prompt reply to its queries.

India is infamous for impunity where majority of cases are committed by the perpetrators who belong to upper castes and go scot-free due to lack of proper investigation by the police. This reality has resulted in only 28.5% conviction rate for crimes/atrocities against Scheduled Tribes in 2020. While India has numerous laws to respect and protect the rights of Adivasis including affirmative laws against their discrimination, its enforcement is very weak due to the prevailing power imbalance in the political and social structures that continue to perpetrate systemic discrimination, racism and social inequity.

The interventions of IRAC with the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) are primarily aimed at establishing accountability for the crimes committed against Indigenous Peoples and ending impunity enjoyed by the accused persons. As a quasi-judicial institution, NHRC holds regular sittings to decide and rule on the complaints and issues timely orders.

The IRAC’s interventions with the NHRC have been highly effective and successful in obtaining positive interim orders in favor of the victims in several cases. The IRAC is the partner of IPRI in India in addressing the criminalization of and impunity against Indigenous Peoples. Through this collaboration, IRAC was able to monitor, document and submit cases of human rights violations to the NHRC and other relevant bodies, as well as undertake awareness-raising and advocacy activities.